Krzysztof Wodiczko in Conversation with Katie Zazenski

We sat in conversation in the fall of 2023 on the occasion of the presentation of Voices of Memory, Krzysztof Wodiczko’s permanent installation at the Hall of Remembrance at the Warsaw Insurgents Cemetery (Warsaw, PL). Our conversation has since continued through spring 2024, both via email and in-person.

KZ: I would love to start with your new piece here in Warsaw, Voices of Memory, and your relation to the uprising. You were born during the war, not long before the Warsaw Uprising, so I’m wondering if you can share a little bit about the personal significance of this work for you.

KW: The Warsaw Uprising happened when I was one year old – I was born a few days before the outbreak of the [Warsaw] Ghetto Uprising. So that means that I cannot remember the war directly. I can only remember war through my parents and grandparents’ stories. Through the physical ruins of Poland, of Warsaw, where I grew up, and also through the human ruins – meaning the traumatized people whose behavior and reactions transmitted and inscribed in me the experience of war. The war was something I could not see but it was something I began feeling; the stories of the Warsaw Uprising were shared more often than the stories about the Ghetto Uprising, because it’s clear that the vast majority of people who could tell this story were not alive. This included one half of my family, [on] my mother’s side – the Jewish side – all murdered in the first weeks of my life. But also members of the family on my father’s side suffered during the war in an incredible way. My father was deported to a Nazi labor camp (at that time the distinction from a death camp was blurred) after being rounded up with a group of friends on their way to join the Warsaw Uprising. The stories about the Warsaw Uprising were around all the time; Christmas Eve dinner conversations were often focused on the family members who perished in the war. 800,000 residents of Warsaw were killed during the Second World War and around 200,000 of them were killed during the Warsaw Uprising. And it was well known to us that the Soviet Army was profoundly complicit in the German Nazi atrocities by not supporting the Warsaw insurgents, but just watching their demise passively from across the Vistula River. So the absence of those people was present – talking about them and telling their stories – but also through the censorship imposed on talking about the Warsaw Uprising. Sometimes people would lower their voice or try not to speak much because authorities in the Stalinist and even in the post-Stalinist period, even into the 70s, didn’t like the topic to be discussed. And so of course, the voices… the multiplicity of voices… interpretations of the uprising could not really come through publicly, it was not easy to discuss it. Internal discussions happened within each family more so than between families.

In this installation, Voices of Memory, you can see and hear the voices. The harmony [of the voices] is a kind of appeal for peace, for the end of wars built upon the polyphony of thoughts, emotional responses and their interpretations. You know, thoughts like should the uprising have happened? Or how to comprehend this massive suffering? Was it justified, could it have been done differently? Was there any possibility to avoid it? But most important is that the narrative surrounding the Uprising, once it became public in the new, post-communist, free Poland, was monopolized by this heroic story that mostly focused on soldiers. Not much was discussed about the situation of civilians, without whom the Uprising could not have lasted more than three days, no less 63. So there was this incredible commitment and contribution and suffering of the population, who were at once the real heroes and heroines and also the victims of this uprising, more so than those who were uniformed and carried weapons, many of whom survived, following the capitulation agreement that was somehow, to a limited degree, honored by the Nazis.

There are some people [in the recordings] who speak about this, who were in the middle of the Uprising as children. The situation of children is very important here. I grew up in the ruins of war, I’m a child of war. And I cannot know what those people directly learned or went through of course, but I know the impact on children a little bit through my own secondary war trauma[1]. You know, my generation, we don’t talk to each other about this, whoever is still alive. There are no words to really explain that secondary traumatic impact.

I think that this installation also speaks on behalf of those overwhelmed by war and the postwar experience, who cannot find the words to speak. And the ideal situation, which is also the plan, is to gradually add more voices – to inscribe new generations of voices into the installation. You know, people often ask me how I feel about working on permanent projects, as most of my art projects have been temporary. My answer is that I don’t mind it, but on the condition that these projects can be changing. It’s very hard to create those conditions when most memorial projects are understood as fixed; sealed, maintained like crypts rather than being responsive to new events and ideas, functioning as living, working memorials.

I am usually extremely critical of my own works, and it takes me a long time, sometimes forever, to digest the risks behind them, including doubts, problems, and difficulties encountered in the process of their making. This time, especially after speaking with those who offered their voice to Voices of Memory, and hearing what people are telling me after visiting the instillation, I feel that this project – so ethically and aesthetically demanding – was a risk truly worth taking.

KZ: I would like to stay with this topic of the voice. I can’t remember exactly where I came across this quote, but you were talking about your process of working with other people. You said something along the lines of “without trust, there is no possibility for my work.” I’m interested to know more about the process of working with these voices, and the people that embody these voices, and how you earn their trust. What is your process? How do you help prepare them, and maybe how do they inform you about their needs? What is this relation?

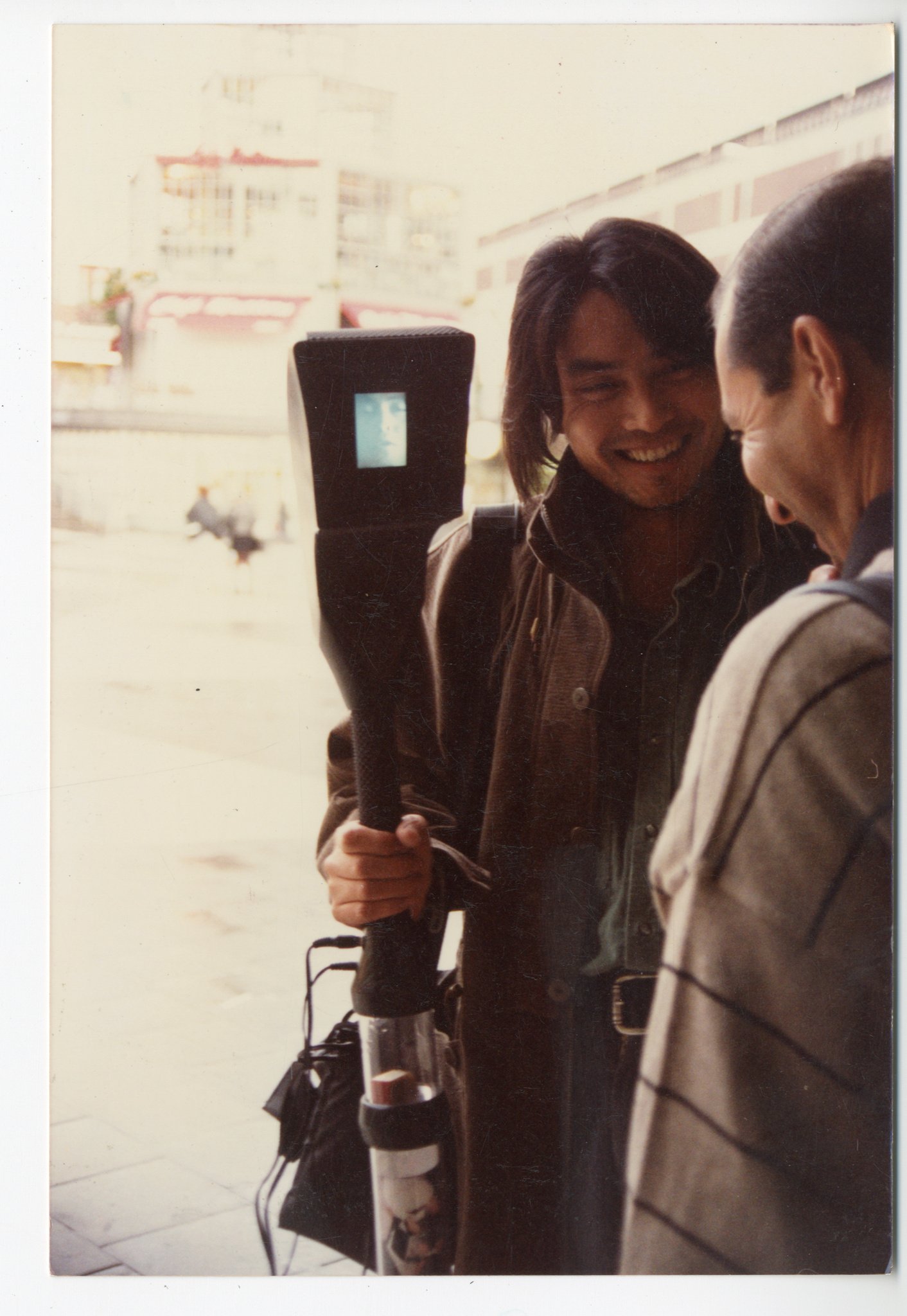

KW: Of course each situation is different, but some things with time, I needed to learn. I needed to learn how to listen. I don’t have a formal education or didn’t go through any courses to learn how to listen, it just became a necessity. Before I began participatory projections with video and sound, animating monuments, I designed a series of special instruments – equipment for strangers, immigrants, displaced people – so they could inscribe their voice into them and then share it with others in public space. The series was presented in many different cities and so took on many different versions of the name – Mouthpiece, Le Porte-Parole, Rzecznik, Alien Staff, Baton d’etranger, Laska tulacza – I needed to first to learn how to openly and actively listen to these people and not to “interview” them. The interview is based on questions, and they could be very legitimate and good questions. But some of those questions are actually painful because they remind people of naive questions which are notoriously asked, or questions that have assumptions in them such as where are you from? This seems a most genuine question, but it can be one of the most painful questions for immigrants because it turns the person into a work of geography, it replaces other questions like what are you doing? What is your thought on this or that matter? What are you working on? Or simply, how are you?

This experience became helpful later when I decided that, with the advent of video projectors that were strong enough to be used in public space, I moved onto engaging monuments as a kind of vehicle for speech, seeing the similarity and interrelation between the monuments and humans, displaced people, or other alienated people who themselves are the living monuments, so to speak, to their often traumatic, lived experiences. My projects are inscribing these people onto/into those historical monuments, the “legitimate” monuments, to help in legitimizing their personal experiences as historical experiences. This project, Voices of Memory, is taking advantage of all my artistic experiences of working in this direction. The building is already a work of art. It’s not my art, it’s the work of Piotr Bujnowski studio, who found the most tactful, respectful, and open form for this Izba pamięci (Hall of Remembrance). I respect the symbolic integrity of this space, interior and exterior. So that’s why I thought that projecting those flames directly on the walls and not onto screens would best engage this architecture, to work together organically with the texture and the volume of the walls that were so well chosen to really help people to feel that they are inside of a space that is solidly enclosed yet at the same time open, towards an exterior experience. It’s like recalling civilians trapped in those various buildings and basements. But also the contrast between being inside and being outside, where children play, where people are walking and there is life; that is also very important – to create a space that is completely different from your everyday enjoyment of life and [to create] a place where you can focus on listening, and see life as something most precious and worth living.

I can recall another interior project at the ICA in Boston. With the use of projectors, I was turning the interior space of the museum into a space of illusion, of being inside a kind of warehouse from which you could sense but not really see what’s happening outside. There were windows, but only at the very top. So you only saw the aftermath of what was happening outside the walls; some dust and debris from explosions. You could hear things but you couldn’t see them. So it was a reconstruction of the particular war event in Baghdad, Iraq. It was an attempt to create, to try to get closer to the experience of civilians trapped inside some building, in the middle of a war zone, not being able to do anything about it. It is also a recreation of an experience of a nightmare – a psychological flashback, a war trauma – which can often last throughout one’s life. This is something that one can hear in Voices of Memory because many of those who participated in this project speak of being trapped in basements as children during bombardment. There are lots of elements in the spoken stories and the flames that refer to architecture and walls – the steps, the broken walls between the buildings from one basement to another. So, thinking about that is quite revealing; when the architecture is engaged in these projections and is animated, you know, it can more effectively invoke memories, the architecture plays a significant role in memory.

Returning to process – most people who chose to be part of this project were kind of encouraged by the Museum of Warsaw and the connections that they have built over years. So in this way, the teams from the Museum of Warsaw and the Profile Foundation functioned as very important intermediate agencies. There were always some intermediate agencies [in my projects]; I would not be able to develop projects in Tijuana, for example, without the organization Factor X, who focused on helping young women, workers of maquiladora assembly factories along the border, to teach them their rights and help them with their existential issues. Without developing trust between this organization and myself, and without their help, there would be no possibility that those people would volunteer to take part in and contribute to the projection. There’s no selection on my part, they must select themselves, and select the project. They choose to support, to take part in it, choose what to say and discuss among themselves or with their families and friends. Or some people didn’t speak at all [before working on this project], so they chose what ought to be made public, what personal experience must become public. I’m bringing up here again, the philosopher Walter Benjamin’s thought that the process of transposing the personal into the historical is a prophetic act. A public interruption of the history of silence about critical human matters. So there’s a prophetic aspect of this; they become agents who speak on behalf of their own experience, but also on behalf of those who cannot speak, who cannot join because they’re no longer alive or they just don’t feel like they’re ready for it or it’s too risky for them. So they become agents. They find that once they hear themselves and their voice is heard and they see and hear the public responding to it, that there is attention, that the public is really listening, then, of course, what they say, what they experience, has a new meaning for them and gives this kind of hope that these unacceptable lived experiences and events will never happen again.

By sharing something painful with others, it helps the person to move on and live in a healthier way with the trauma. It is nearly impossible to completely cure oneself from trauma, but one can live with it, moving on with one’s life in a healthier and more pro-active and socially productive way. So the mission here was to speak on something that is so hard to understand; it takes great effort just to find words and expressions for unspeakable experiences. And the more that this happens, the more it is also good for them. The more effective (socially and culturally) such a project can become. Without the emotional and intellectual investment of witnesses and survivors, there would be no Voices of Memory. Without those who speak, there would be nothing to talk about. They are the living monuments. And that’s why the voice is very important, because the voice here is not only about what is being said, but also how it is said; there is a certain emotional charge and a certain kind of tone that implies that there’s something deeper. In Polish there is this word przeżycie, which is very hard to translate to English. It could be translated in three words: lived-through-experience. So this is what is being transmitted, emitted, and perceived, I hope, by the public.

I think this Hall of Remembrance where Voices of Memory is located is a very central place in Warsaw’s collective memory, even if it’s not physically in the center of the city. This project is also central to my artistic life journey because it capitalizes on and puts together many of my attempts in other projects and experiences, in trying to create something that helps some people to open up and speak, and for others to come closer, open their ears and listen – to create a space and a situation in-between – a communicative artifice.

KZ: As you’re sharing these stories I feel the emotion of it and the life that comes through for you in these works. And it reminds me of something, I believe it was in relationship to your project in Tijuana, but you said you have this role of a mother, and you had this reference of when talking about the people who are making these recordings, who are telling their stories, that you are protective in this process, like a mother. And I thought that was fascinating for so many reasons, and incredibly beautiful and powerful, too, how you’re speaking about this element of nurturing and giving space.

KW: This role of the mother is related to Derek Winnicott’s concept of the “good enough mother”. He also has another important concept of the “transitional object.” This transitional object could be understood here, just using that term invented by Winnicott, as something that comes to the project’s potential participants from outside, like myself and the project itself, and that’s first being treated with suspicion, as a danger of being manipulative and tendentially “framing” them. As something that demands resistance [from them] as this project and this “artist” Wodiczko, whoever he is [laughs]… could feel like an invasion. But there is also an opposite process in which through discussions and questioning, they gradually inscribe this project into their inner world as something psychologically and socially useful for them and others like them. In this way, the project becomes no longer just mine and in some way, becomes theirs. In such transitory processes and situations, I feel that the term “participant” seems inappropriate. I prefer “project partner” (wspólnik projektu) or [laughs] “project accomplice.”

But this particular installation [Voices of Memory] probably invites an even more transitory condition because it is a polyphony of voices and there is a possibility to say, okay, I am in agreement with this voice, or I question that approach, or I still have questions that were not even raised here. A critical response to this installation might really add to the value as a trigger of more discussions. Because memory should be understood here – I mean the kind of understanding of memory behind this project – as a discursive process, as a work of memory, meaning “working through” what happened. These should not be the “melancholic” ways of memory as Freud would call it, that is through the repetitive and endless recollection of painful pasts, or worse, the ways [of memory] leading to the repetition of such tragic pasts through martyrology, through a cult of martyrdom (martyrologia in Polish). This tragic melancholia is something that is still a painful aspect of Polish and Central European culture that was so importantly challenged by Maria Janion in her work on Polish romanticism and Polish martyrology. .

There are voices of suffering in this work. But in them, there is an attempt to think through the tragic experience and its context as a way of challenging the danger of perpetuating such tragedies. In the process of recalling the issue is not only remembering as an act of not forgetting, but also what is important is how to remember. You know, recalling it critically is also about seeing a vision of the future, and that’s why it’s very important that there will be young people coming to hear and see this installation, also with their parents and grandparents. It’s an obligation on the part of parents to openly speak to their children and grandchildren about what happened. And on the part of children is the obligation to ask questions and to demand open discussion. Children hae an intuitive need for this. But the role of this memorial place, the educational role, the pedagogical role, is also to inspire, protect, and animate such thinking and discussion. This is already happening through the educational space and program of the memorial, which has been designed for this.

KZ: But how do we make space? How do we have space for remembering and honoring and teaching and learning while there are active and new wars raging, while new memories of war are forming?

KW: If it is not abolished, there will be more and more people killed in war. And the thing is that cities are the primary targets of missiles and bombs and military attacks as today in Gaza and not long ago in Grozny or Dresden, Tokyo and Hiroshima and Warsaw. Today, with more and more cities with populations over 10 million people, and the increasing threats of the concrete use of nuclear weapons, civilians even more than soldiers become the greatest human toll of war. To end wars we must change the way of thinking about our disputes to resolve them without violence and armed conflicts. So you’re right, this situation becomes an even more demanding context for Voices of Memory.

More and more memory places should be built. Not those who are nationalistic, with this narrative of martyrology and revenge, but more about building anti-war and peace-building connections between countries and cities. And I don’t think the type of work I do is going to resolve the issue or immediately have an impact on ending wars, but it builds up a different culture, a different consciousness for wars, a different way of remembering wars, previous wars, [which will] definitely help people to resist following and perpetuating the militaristic and chauvinistic patterns of culture because most national cultures basically are still cultures of war. History is being measured, paced by wars – what happened between the wars, during the war, after the war – the behavior of people, their identities and their kind of character even is evaluated by the way they behave during and in relation to wars. I think there should be different way of expecting people to prove their own value or their own identity. So the problem becomes bringing up the memory of those who who learned by direct and secondary experience what war really is, what it does to people; the memory of these prevented wars, who contributed to building peace, who actually call for different way of thinking – [to build monuments to] those who have worked to secure a peace that is not already pregnant with war.

KZ: You mentioned the pedagogical role of your work; I’d love to know more about the role of education and the role of teaching in your work, and in your practice as an artist.

KW: I think that my artistic work is somewhere in between art and design. There is also some urban pedagogy there when it comes to memorials and bringing different narratives to them, and teaching them how they should speak of present time and to the future. I’m using projections as a means of projecting things via sounds and images. But also creating conditions for people to become projectors, and in a sense, to become educators as well, because I think that every educator is a projector. It’s also a different thing when you create educational situations because in such projects, one must assume the role of the “good enough mother” rather than giving lectures and instructions all the time. Many of my projects were curated or were helped or organized with educational departments in the museums and art centers I have worked with. I value very much working with those departments specifically because they often engage the Public Space in a discursive way, of learning through new methodologies of urban pedagogy and art education.

I have taught in many institutions in North America and Europe on monuments, collective memory, public space, art and trauma… So in my thinking, the fields of political theory, social psychology, trauma therapy, education, public art, or design, they are all connected. The world is too complicated to work alone. These fields overlap especially when it comes to socio-aesthetic work and art in public space that involves media.

KZ: I think this is a good segue into the last thing that I would like to ask you about, which is somehow an anthesis of working and learning together – the feelings of solitude that come from darkness. One thing I was really struck by when visiting Voices of Memory was the darkness. And it made me think about your projections, and the fact that we need to experience most of your works in darkness. We have very different physical and psychological relations and circumstances that occur in or because of darkness.

KW: Technically of course, projections benefit from darkness by principle, but there’s lots of connections and correlations. We have the idea of the uncanny (Freud again), something that’s supposed to be kept in the dark but comes to light…and then we have the darkness of interiors. [This piece] is a very special projection exactly because it is an interior projection. It becomes a kind of a metaphor for our own interior, our inner worlds. So we are inside, and there is an outside world from which we are isolated, or self-isolating.

The beginning of my video projections was in Kraków. That was the first time I got the opportunity to use the newly arriving equipment, powerful video projectors from Belgium that were brought for the Andrzej Wajda art festival. The projectors were there to project his films outdoors, in the public space, and I realized that I could do it, too. I could use them for the first time; animating a monument not only with images but with sound and motion, and I realized that with the use of video, the projection can bring to light these night situations in urban environments, so let’s focus on what’s happening at night. The nightmares; all the recollections, the violent situations at night in the city – the domestic abuse, all of those scenes related to narcotics, sex work, and so on. I realized that night was important not just because it’s dark, but because there are things hidden at night that ought to be made public and ought to be illuminated. So in that sense, projection may function as a sort of “illumination.” So you’re bringing in truth, light, darkness, those are the terms used metaphorically in many, many situations when it comes to public education, when it comes to truth telling – the parrhesia – you know, the kind of disruption of what’s kept in the dark; video comes with sound, so it’s also a disruption of the silence of the city. So speaking at night about what actually is happening in a person’s life and in other people’s lives, of which nobody wants to know, this is very big. It speaks through its silence, it lets the silence speak.

But when it comes to interior projection, when you are inside, enclosed, the projected images could reveal something from the outside world. Or also it could reveal, at the same time, your own limited capacity to know, to see what’s happening in that outside world. This was the idea of the 2009 projection in the Polish Pavilion at the 53rd Venice Biennale, Guests, or the first interior projection I made, Real Estate Projection at Hall Broom Gallery in New York in 1987. In those projections, as I mentioned before, the wall itself is a part of the project and must remain visible. And as in Voices of Memory, its presence and its texture must stand as something in-between what’s being said – what is that emotional dynamic in the flame and you, the viewer-listener. This helps you to remember that you will never be able to pierce through the wall and fully understand what those people who speak have experienced, and that you must not pretend that you can identify with such experiences. The wall, as a kind of important thing in-between that not only prevents you from empathizing with the projected traumatic words too quickly, but also protects those who speak these words from your listener’s gaze and from the false assumptions that you can truly understand what they are saying and what they went through. What it also means is that we need more then what this projection can do, because we are still locked here, in this dark space. We must leave this dark interior and do something to change the situation in the outside world, for the sake of those whose voices we hear, for all others like them, and for ourselves.

[1]Referring to the collective and generational trauma that is absorbed indirectly.

Artist: Krzysztof Wodiczko

Exhibition Title: Voices of Memory

Venue: Hall of Remembrance, Warsaw Insurgents Cemetery

Place (Country/Location): Warsaw, Poland

Dates: 2023, permanent installation

Produced by: Museum of Warsaw